Almost Tilings of the Unit Square (Part 1?)

Published:

Note: This post first appeared on a now defunct blog on January 19, 2019

The following problem came from an old qualifying exam.

We’ll say that an almost tiling of the unit square $[0,1]^2$ by an open set $U$, is a collection of disjoint sets $\displaystyle{{a_iU + b_i}}$, with $\displaystyle{a_i>0, b_i\in \mathbb R^2}$, such that the following two conditions hold:

- $\displaystyle{a_i U + b_i \subset [0,1]^2}$,

- $\displaystyle{[0,1]^2\setminus \bigcup_{i}}(a_i U+b_i)$ has zero area.

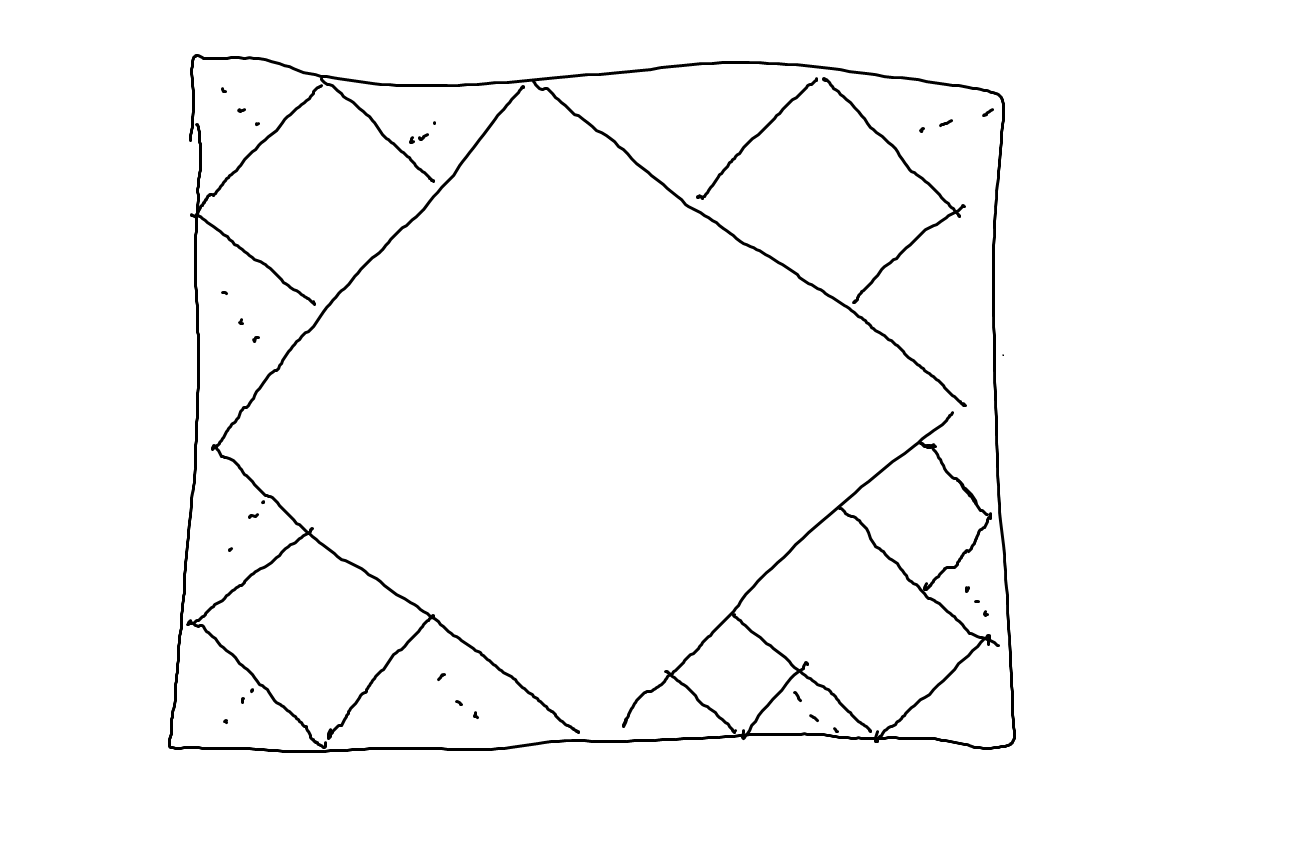

Throughout the post I’ll refer to the sets $a_iU+b_i$ as tiles, and the numbers $a_i$ as the diameters of these tiles. Claim: For any almost tiling of the unit square by the diamond

\[D=\{(x,y)\in \mathbb R^2\colon |x|+|y|<1\}\]we have $\displaystyle{\sum a_i = \infty}$.

A diagram of the setup is pictured above. One thing worth noting is that away from the boundary of the square we are able to cover a region with finitely many such diamonds. It follows that the problem we run into if trying to almost tile the unit square while having the sums of the diameters converge must occur at the boundary.

What’s rather interesting then is that there is a solution to this problem that relies on almost no geometry, and is mostly reliant on the Borel-Cantelli Lemma from measure theory (there’s a very slick proof of the statement in the Wikipedia article).

Define $E_i$ to be the projection of $a_i D + b_i$ onto the first coordinate. Then we have that $m(E_i)=2r_i$. By Borel-Cantelli, the desired result follows if the set of points which lie in infinitely many $E_i$ has strictly positive measure. Let $B={\text{points in finitely many }E_i}$. One way of describing this set B is as the collection of points on the bottom edge of the unit square which have finitely many diamonds lying above each of them. For each point $x\in B$ there are two possible cases.

There is a tile of which x is on the boundary. Since the boundary of a tile can intersect the bottom side of the unit square in at most one point, and there are countably many tiles, it follows that there are at most countably many x which are of this type.

There is some set of positive length lying above x which is not contained in any tile. Take $B_\varepsilon$ to be the set of such points with gaps bigger then length $\varepsilon$. If $B_\varepsilon\subset [0,1]$ had positive length, this would give a set of positive area not contained in any tile, a contradiction to our definition of almost tilings. It follows that $B_\varepsilon$ has zero length, and so combining with case 1, we see that B has zero length, and our claim follows.

The proof above does not depend at all on the fact that we chose our tiles to be diamond shaped. The only geometric fact that this proof relies on is that the boundary of a tile can intersect a side of the unit square in at most one point.

For example, we can extend the proof above to show that almost tilings by circles, ellipses, triangles, regular hexagons, nonrectangular quadrilaterals, etc., will have the property that sum of the diameters will diverge. This leads to a natural question:

With what sets can we almost tile the unit square, in such a way that the sum of the diameters converge?

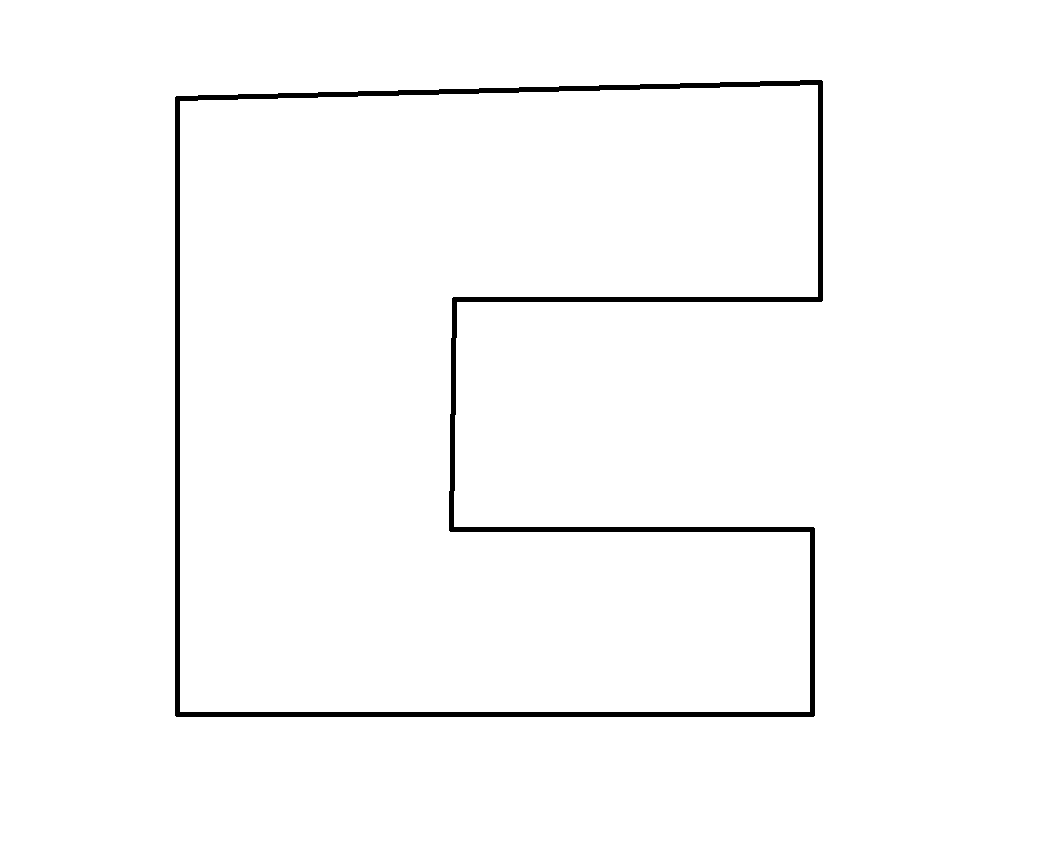

We can of course almost tile the unit square in such a way by a square with parallel sides, and more generally by a rectangle with parallel sides and a rational aspect ratio, since we can construct such an almost tiling using finitely many tiles. Another such example is the square horseshoe pictured below. If we choose the dimensions of the figure to be correct, we may nest these horseshoes, each with 1/2 the diameter of the previous, and so the sum of the diameters will converge to 2.

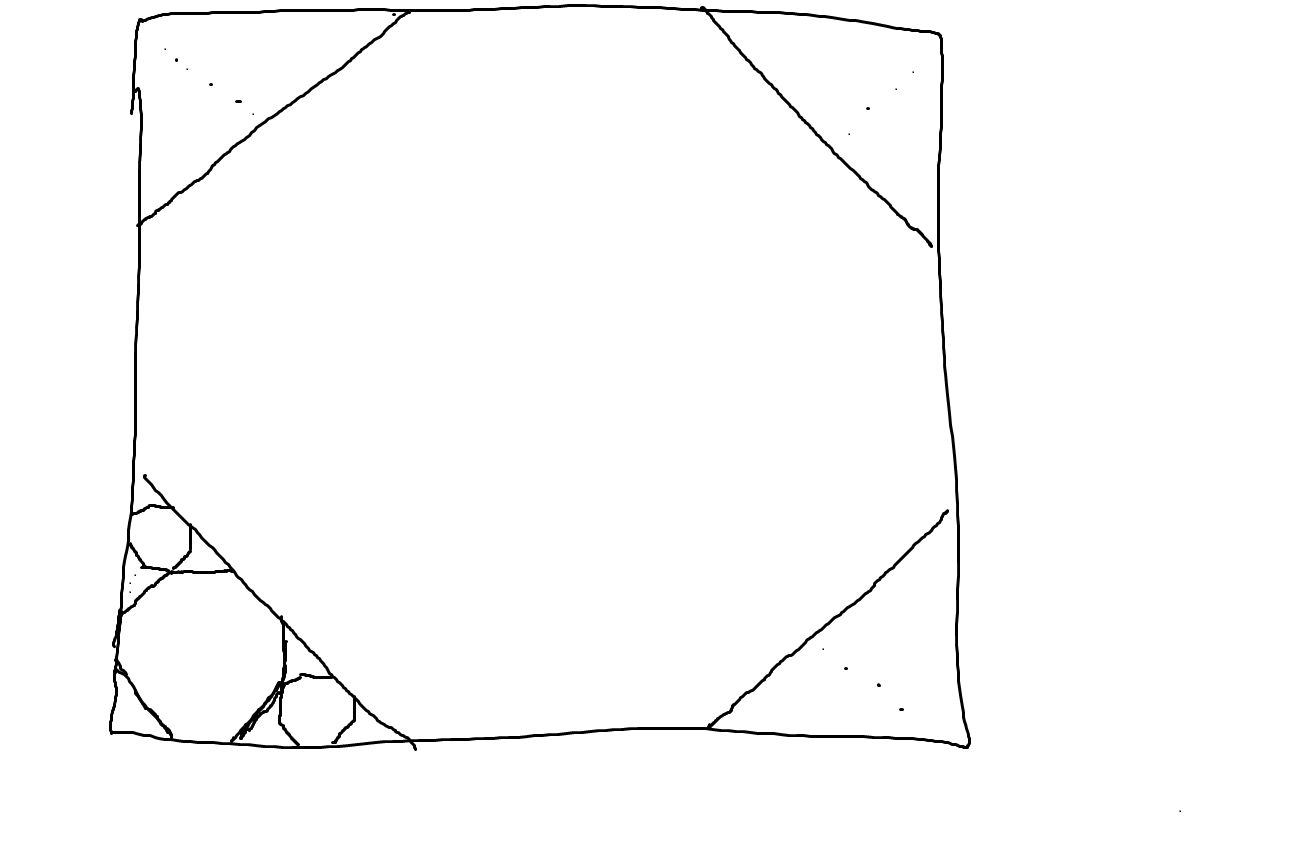

But what about something that admits a less regular tiling? For example, an almost tiling of the unit square by regular octagons is shown below.

The tiling is made by adding the largest possible octagon which does not intersect any previous ones. Some brief analysis shows that in this case the sum of the diameters will diverge. This doesn’t tell us that this will be the case for all possible tilings by regular octagons however. For now I would like to conclude with the following (perhaps overly ambitious) conjecture.

Conjecture: Let U be an open, convex set in the plane. There is an almost tiling of the unit square by U such that the sum of the diameters of the tiles converges to a finite number, if and only if U is a rectangle with sides parallel to those of the unit square, and with a rational aspect ratio.